In June 1934, when James Perry Wilson walked into the American Museum of Natural History on his first day of work, he was almost 45 years old. He had already had a 20 year career as an architectural draftsman and designer and was fully formed as a mature landscape painter. At the architectural office, he had immersed himself in a high-brow bohemian culture of well-educated, creative thinkers and was, himself also one of them. His plein air painting work increased after he was laid off as an architect in 1932 and especially after he got his foot in the door with a job possibly painting natural history dioramas. From that time on, Wilson was certainly starting to think about how to paint large landscapes on curved backgrounds. He already knew, before he walked into the museum, that there would be a problem with distortion from painting landscapes on a curved surface. And, he knew that correcting it mattered. His immense knowledge of projection perspective used in architectural renderings was an immediate solution to the problem. He came with that idea at the ready. Within six months, Wilson suggested to his mentor, William R. Leigh, that he grid the background to adjust for perspectival distortion. (Painting Actuality, The Diorama Art of James Perry Wilson, p110). It’s astonishing he would suggest it to the artist who had been to Africa with Carl Akeley and had already painted several diorama backgrounds. It points to the confidence he had in the efficacy of his gridding method.

Wilson knew on a cellular level, painting techniques to enhance the illusion of depth, to use transition of color values to achieve a sense of atmospheric perspective. He knew about the transition of color in clouds as they recede into the distance, He had a strong determination to not use black in his palette because of its deadening quality. He had done all this repeatedly in his smaller plein air paintings and knew it would work equally well on a large diorama background.

While James Perry Wilson had studied painting techniques and architectural perspective for his entire adult life, he also had immersed himself in classical music and especially the music and operas of Richard Wagner. There are 20 pages of letters that Wilson wrote to his friend, Thanos Johnson about Wagnerian concerts, recordings, and books. It is clear that Wilson spent much free time listening to Wagner. He told Thanos he owned over 1000 classical music records. He went as far to hand-transcribe five themes from the Ring for Thanos to practice on a recorder that Wilson bought for him. Wilson was a serious student of the piano in his youth and college years. Wilson worked in Bertram Goodhue’s office from 1914 to 1932. Goodhue was producing some of the high visibility neo-Gothic churches in the early 20th century. He was making waves in the architecture world.

He wrote the following to introduce the music:

This theme is often associated with the person of Wotan, as well as with his castle. For instance, in Act I, where Sieglinde tells Siegmund of the strange old man who appeared at her wedding and thrust the sword into the tree, the orchestra swiftly sings “Walhalla,” and we know that the stranger was Wotan himself. I give the theme in its full form, as it appears at its first appearance in “Das Rheingold.” In “Die Walkure” it is usually in a shorter form.

Then there is “The Sword,” always clean-cut and keen in the brasses:

Remember how, in Act I, when Siegmund, alone after the exit of Hunding and Sieglinde, apostrophizes his father—“Wake! Wake! Where is thy sword?”—every time the fire on the hearth flares up and shines on the sword-hilt, this theme is heard? Often as I have heard and seen it, it always gives me a thrill.

Bertram Goodhue thought on an expansive scale about church architecture. He wanted his churches to appear distant in time and place and to excite the imagination by their strange effect. Wagner’s opera was also an important analogy Goodhue used to frame his ideas. The ecstasy of the spirit operating through the medium of beauty, was Goodhue’s ideal in church architecture. Wagner’s large-scale operas are an exploration of the mystery of the breach of the divine into the human. For Goodhue, this experience of the divine as the power that stands behind everything, was not verbal, but visual and aural; its setting was not life, but art. Translated to his churches, Goodhue created settings of stained glass, embroidery, metalwork, sculpture, and painting as one all-encompassing work of art that was truly Wagnerian in its integration of the arts as the visible expression of the religious energy of the church.

Wilson was one of the players in Goodhue’s architectural orchestra creating the material embodiment of this aesthetic thinking. Wilson and Goodhue shared together their love of Wagner and both were accomplished piano players. Wilson and others in the office would have engaged with Bertram Goodhue in conversations that were grounded in the Wagnerian aesthetics of their architectural work.

This is the artistic training and intellectual background James Perry Wilson brought to the American Museum of Natural History in 1934. The Wagnerian narratives were as strongly embedded in Wilson’s mind as were his painting techniques. I believe all aspects had an impact on how Wilson produced and thought about his diorama work.

How could he not use Wagnerian vocabulary to describe what he saw when he first walked in front of those magnificent dioramas? They were large scale, expansive theatrical settings with superbly romantic landscape paintings. Taxidermied, trophy-sized mammals and birds of the jungles, forest and desert cavorted with each other in an environment unspoiled by human presence. The faux habitat looked as alive as if he had walked into it in a dream. Talk about ecstasy! Bertram Goodhue had never been able to pull something like this off in his churches! There was enchantment with no reliance on religious content, just a firm commitment to scientific veracity and to the education of the public.

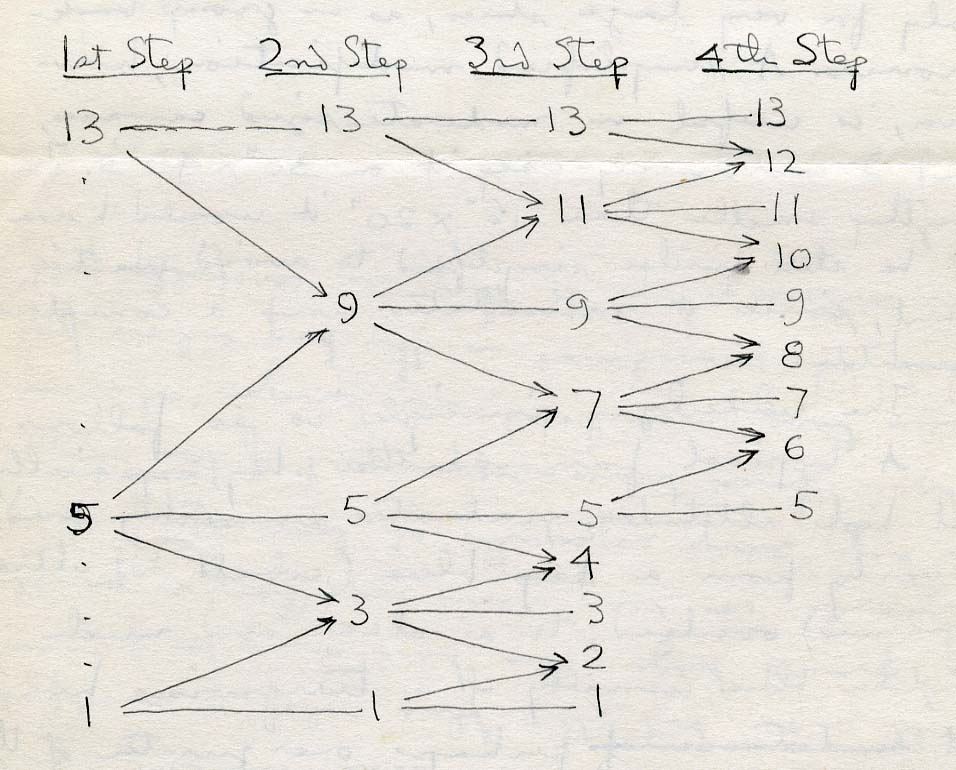

The multiple complexities of James Perry Wilson’s creations, the projection perspective, a field of view carefully planned to match the field of view in the landscape, his control of values and color to create atmospheric perspective, the grids on his photographic panoramas, the thirteen bands of color to produce luminous skies, his collaboration with foreground artists and the higher hues he painted at the tie-ins to create a seamless “jump” from two dimensions to three. He used the curve of the dome of the diorama to enhance the feeling of a canopy of tree tops, and no black was used in his palette to get the brightest colors. All these techniques were employed together to create the illusion similar to or even beyond the spirit that Goodhue and his fellow architects were trying to imbue in their buildings. This was the level James Perry Wilson was reaching for in the dioramas and a level that he knew was attainable with the knowledge and the tools he had at his disposal. He would go on to create over the next twenty-three years, a realism in the dioramas beyond anything seen before. Much like Wagner’s composition of music, Wilson was putting his orchestra together, a multipart composition, to create a uniquely Wilsonian grand exposition that defined his dioramas.

To read more about James Perry Wilson and to see photographs of his dioramas and paintings see:

Painting Actuality, The Diorama Art of James Perry Wilson Author, Michael Anderson,Self-published: Bookbaby, 2019

Request to purchase this book can be sent to Michael Anderson at: michael.anderson0203@gmail.comor calling or texting at 203-554-3002

The book is also posted on this blogsite